In the spirit of the

previous post by Sean Carr, we'd like to begin with an excerpt from Charles MacKay’s

Memoirs of Extraordinary Public Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. In the chapter dealing with John Law’s Banque Royale we find the following reasoning emanating from the mind of France’s then Regent Duc D’Orleans:

“If 500 million of paper (money) had been of such advantage, 500 million additional would be of still greater advantage.”

It is a curious fact that almost 300 years after that statement was made, we can all sort of sense what the Duc must have been thinking, even if we don’t know much about John Law and his exploits. But curiosity is not the reason we started with this quote. The real reason is in that it illustrates one of the most vicious fallacies in our thinking about the world around us: linear extrapolation. Some quantity appears to have done some good; twice as much should be twice better. Whether it is fortunate or not, the world is not the linear place. Double the quantity of a good thing, and the results may not be what you expect. This goes for exercise, food, alcohol, medicine, and even leisure (though the last one is debatable).

So, today we are wondering: are the central banks around the world going to overdo it? Are we going to get inflation in place of the credit crunch? We don’t know, but in the world of risk it pays to think about the possibilities. Before we offer our analysis, let us be clear about what we are not intending to do. We are not going to argue whether it was worth to take the stimulative steps that have been taken. If anything, we tend to agree that the prospect of financial meltdown was so real that some drastic measures were necessary. Our purpose is to merely examine where we are, where we are likely headed, and how to prepare for it.

Where We Are

Some of us may have thought that the stabilizing actions of the Fed were of the improvised fire fighting variety. In fact, Ben Bernanke has outlined many of the measures currently taken as early as 2002

in a speech before the National Economists Club in Washington, D.C. In it he described the steps that would be taken in a zero Fed Funds Rate scenario (we bring our apologies for the extensive quotation, but after all if you want to know where you are it is worth asking the driver):

“Because central banks conventionally conduct monetary policy by manipulating the short-term nominal interest rate, some observers have concluded that when that key rate stands at or near zero, the central bank has "run out of ammunition"--that is, it no longer has the power to expand aggregate demand and hence economic activity…

However, a principal message of my talk today is that a central bank whose accustomed policy rate has been forced down to zero has most definitely not run out of ammunition…

Indeed, under a fiat (that is, paper) money system, a government (in practice, the central bank in cooperation with other agencies) should always be able to generate increased nominal spending and inflation, even when the short-term nominal interest rate is at zero.

The conclusion that deflation is always reversible under a fiat money system follows from basic economic reasoning. A little parable may prove useful: Today an ounce of gold sells for $300 (remember, this is 2002), more or less. Now suppose that a modern alchemist solves his subject's oldest problem by finding a way to produce unlimited amounts of new gold at essentially no cost. Moreover, his invention is widely publicized and scientifically verified, and he announces his intention to begin massive production of gold within days. What would happen to the price of gold? Presumably, the potentially unlimited supply of cheap gold would cause the market price of gold to plummet. Indeed, if the market for gold is to any degree efficient, the price of gold would collapse immediately after the announcement of the invention, before the alchemist had produced and marketed a single ounce of yellow metal.

What has this got to do with monetary policy? Like gold, U.S. dollars have value only to the extent that they are strictly limited in supply. But the U.S. government has a technology, called a printing press (or, today, its electronic equivalent), that allows it to produce as many U.S. dollars as it wishes at essentially no cost. By increasing the number of U.S. dollars in circulation, or even by credibly threatening to do so, the U.S. government can also reduce the value of a dollar in terms of goods and services, which is equivalent to raising the prices in dollars of those goods and services. We conclude that, under a paper-money system, a determined government can always generate higher spending and hence positive inflation.

Of course, the U.S. government is not going to print money and distribute it willy-nilly (although as we will see later, there are practical policies that approximate this behavior). Normally, money is injected into the economy through asset purchases by the Federal Reserve. To stimulate aggregate spending when short-term interest rates have reached zero, the Fed must expand the scale of its asset purchases or, possibly, expand the menu of assets that it buys. Alternatively, the Fed could find other ways of injecting money into the system--for example, by making low-interest-rate loans to banks or cooperating with the fiscal authorities…

If we do fall into deflation, however, we can take comfort that the logic of the printing press example must assert itself, and sufficient injections of money will ultimately always reverse a deflation…

The Fed can inject money into the economy in still other ways. For example, the Fed has the authority to buy foreign government debt, as well as domestic government debt. Potentially, this class of assets offers huge scope for Fed operations, as the quantity of foreign assets eligible for purchase by the Fed is several times the stock of U.S. government debt.”

Alas, the alchemists never found the philosopher’s stone and gold is still in limited supply. Today’s financial alchemy of central banking does not even require a printing press; the money is created electronically. Credit markets now appear to have stabilized, and economic data in many parts of the world shows signs of increasing output, so what is next?

Where We Are Headed

One of the best books on inflation is Milton Friedman’s

Monetary Mischief. In it he attempted to answer many of the questions that we are asking. What would happen, he asked, if a helicopter were to simply fly over and drop the money from the sky? (Ben Bernarke also used the helicopter metaphor.) The precise sequence of events is impossible to predict, but there are some generalizations that can be made from empirical evidence.

In the short run, according to Friedman, the increase in money supply will show up in an increased output without affecting the price level. Interest rates also decrease in the short run. This short run has usually lasted 6-9 months. The effect, however, shows up in the rising prices in the longer run, usually 12-18 months after the short run effects have commenced. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect inflation to pick up within the next year or two. It is impossible to suggest the level of inflation, because the adjustment may be drawn out with ups and downs along the way. The matter is complicated by the Fed’s decision to stop reporting M3 figures, which would help in gauging the level of the brewing inflation.

How Long Will The Inflation Last (Or Will The Real Paul Volcker Please Stand Up)

Just as there is a lag between the increase in money supply and the effect on prices, so there is a lag between the implementation of the inflation fighting program and reduced inflation. In other words, once started, inflation cannot be stopped quickly. It took Paul Volcker at least two years to stop the inflation in the early 80s at the cost of raising the short term interest rates as high as 18% at one point.

However, in our present situation, it will take considerably longer. The reason is that unlike the early 80s, both the U.S. Government and U.S. Consumer are heavily indebted. The net savings rate is around zer0, and U.S. debt is close to $10 trillion not counting the implied guarantees. In such a scenario, significant increase in the interest rates would be difficult to say the least. Continued increase in the money supply on the other hand reduces the real debt load. To summarize, inflation will likely go on for a while.

Stress Testing The Inflation

If the risk model we are using (FactSet offers models from Barra, Northfield, R-Squared, and APT) had history back to the early 70s when high inflation was last observed, this stress test would be as easy to set up as any factor test (for example a 30% decline in S&P financials). To set up the inflation stress test we would simply find the data series for CPI and use Stress Testing horizon feature to specify something like a 10% increase over 12 months. However, the only model with that much history is Barra’s U.S. Long-Term Model (USE3L). Here is the result:

As we can see, the nominal return to S&P 500 is almost exactly flat in our test. The four worst losers are Automobiles and Components, Banks, Consumer Durables and Apparel, and Diversified Financials. The biggest winner is Energy, followed by Pharmaceuticals, Food, Beverage and Tobacco, and Health Care Equipment and Services. It is important to remember that these are statistical predictions, the order and magnitude matter, while precision does not. -14% and -17% are likely to be statistically equivalent.

But most risk models do not go back before the 1980s. How could we possibly use stress testing to ascertain the effect of inflation on a given portfolio when nothing in the recent history of the risk models gives us any idea of what a high inflation environment looks like? In general, stress testing the relationships that have not been observed or have been significantly altered in the recent history is difficult. However, it is certainly possible. As we were doing

empirical research in the Fall '07-Spring '08 on our stress testing engine, we asked the following hypothetical question: How would we stress test the effect of a nationwide decline in housing prices on a stock market portfolio? Our situation at that point with respect to declining housing prices was similar to our situation today with respect to rising inflation. Both did not yet take place and were not observable in the recent model history. We had to make an expert judgment on finding the market metric that was both observed and highly related to the object of our study. As a result, we chose to stress test the S&P Financials decline in place of the housing decline judging that the latter if it occurs is bound to be shortly followed or preceded by the former. We did have significant financial declines in our available sample, particularly the LTCM related mini credit crunch in 1998. Subsequent events of Fall 2008 showed that our conjecture was valid and was giving valuable results approximating well the effects of declining housing market (see

Portfolio Crash Testing).

Applying this logic to the stress testing of inflation, we designed the following test which uses the multiple shock functionality of our system: Gold up 40% and simultaneously Case-Schiller Real Estate Index flat 0%. We believe that such a test will approximate the conditions likely to be observed if inflation picks up significantly. The Inflation-Gold relationship is obvious, but what about flat Real Estate prices? Why are they necessary? The reason is that we want to separate two types of inflations: broad Consumer Price Inflation from the Asset Inflation. The money supply started growing before 2008. In fact, the last reported growth rate for M3 was around 18% in 2006. Throughout the early 2000s, money supply growth was mostly pushed out of consumer prices and into commodity and asset (financial and real estate markets) by the consumer price deflation exported from China and other low-cost producers. The environment that we want to test is the broad consumer inflation and that is why we explicitly add the zero real estate growth parameter. The result using Northfield Global Model is shown below:

The best performer again is Energy, just as expected. The next best is Utilities, followed by Pharmaceuticals, which paints a slightly different picture. The worst performers are again Automobiles and Components and Consumer Durables along with Retailing. The Real Estate stocks are down slightly likely because

flat nominal Case-Schiller Index actually means some loss in real terms for the housing market. It could be argued that an alternative specification could be that the real estate prices could go up in nominal terms staying flat in real terms.

The next step after examining the portfolio level impacts of the stress test should be to go into one of the asset level reports in the Portfolio Analysis, for example, the Weights report. This would allow for the decomposition of portfolio impacts within the portfolio subsectors and industries and down to security level.

As we have seen, it is possible to go beyond traditional factors test to approximate factor shocks that have not been observed in our sample. We close with the observation that many of the events considered to be Black Swans (completely unpredictable in substance or timing) are really more of Grey Birds (anticipated by some experts in substance, but unpredictable with respect to timing or specific sequence). The fact that the timing or sequence of shocks is not known should not deter us from having them on our Stress Testing radar.

Additional contributions by Chris Carpentier, FactSet Portfolio Product Developer

To receive future posts by e-mail, subscribe to this blog.

Short-Term Volatility

Short-Term Volatility

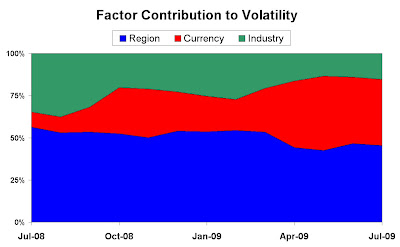

The chart shows how the nature of the risk over the last couple of years has varied in terms of the systematic contribution.

The chart shows how the nature of the risk over the last couple of years has varied in terms of the systematic contribution.

The reduction in the average return reflects not only the recent downturn but also excludes the postive market run through 2004. The big change though is in the standard deviation of those returns, the value almost doubling.

The reduction in the average return reflects not only the recent downturn but also excludes the postive market run through 2004. The big change though is in the standard deviation of those returns, the value almost doubling.

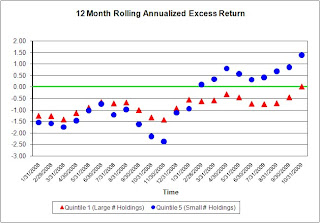

The results show simulation B having a higher alpha, lower beta, and higher overall IR. Also note the standard deviation of portfolio returns is lower when using the AGR score (i.e., less portfolio risk).

The results show simulation B having a higher alpha, lower beta, and higher overall IR. Also note the standard deviation of portfolio returns is lower when using the AGR score (i.e., less portfolio risk).

The overweighting of the S&P500 in Information Technology would have a negative relative effect with the strong Dollar affecting the returns of large exporters such as IBM, Apple, Microsoft, etc. The relative underweighting of the S&P 500 in Financial stocks (e.g., 14.9% vs FTSE 100 >21%) where through globalisation most have a large exposure to the U.S. (e.g., HSBC and Barclays), would generate a positive return, as would the Materials sector where the low exposure to commodities (all priced in USD) is a boon (i.e., no exposure to BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto, etc.)

The overweighting of the S&P500 in Information Technology would have a negative relative effect with the strong Dollar affecting the returns of large exporters such as IBM, Apple, Microsoft, etc. The relative underweighting of the S&P 500 in Financial stocks (e.g., 14.9% vs FTSE 100 >21%) where through globalisation most have a large exposure to the U.S. (e.g., HSBC and Barclays), would generate a positive return, as would the Materials sector where the low exposure to commodities (all priced in USD) is a boon (i.e., no exposure to BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto, etc.)