While the two approaches to performance attribution explain the same excess return, they are conceptually and mathematically different enough that they will frequently produce inconsistent results. Since the point of analyzing from both perspectives isn’t to instantly validate each other, this kind of discrepancy shouldn’t frustrate you. In this post, I will offer some suggestions on how to proceed when you encounter these types of differences. Our most experienced users jump on these results as an opportunity to gain insight. You can too.

To begin, I should review my terminology. Brinson attribution refers to performance attribution based on active weights. There are different variations, but the effects usually include allocation, security selection, currency, and potentially others. In contrast, risk-based performance attribution decomposes excess return to active risk factor exposures. This is also considered a multi-variate attribution.

Each performance attribution approach has important strengths and weaknesses. In particular, the critical shortcoming of Brinson attribution is that it doesn’t prevent you from selecting a report grouping irrelevant to the portfolio construction process. When mistakenly done, the analysis is not meaningful at best and misleading at worst. Risk-based performance attribution is a good complement to Brinson attribution because it doesn’t suffer from this weakness, and inconsistent results warn you to rethink your report groupings.

Let's review a sample analysis using a fictitious portfolio to help demonstrate the issue (or opportunity). The analysis below compares performance attribution for the last four quarters using both attribution methodologies simultaneously.

It's clear that the two methodologies differ significantly. The Brinson model attributes the excess return almost entirely to security selection. In contrast, the risk-based performance attribution indicates excess return is attributable to both systematic risk exposures and security-specific decisions. Now what?

To gain a deeper understanding, first identify what risk factors were the primary sources of (or detractors from) excess return. This is most concisely studied through the following report which reveals size bias as the largest contributor to systematic excess return.

Now, lets use what we learned from our risk-based performance attribution and change the report grouping from sectors to market cap bins.

Now, lets use what we learned from our risk-based performance attribution and change the report grouping from sectors to market cap bins.  This change of grouping clarifies how the portfolio was constructed (whether intentional or not). In retrospect, our mistake was the decision to group the report by sector. In this case, the portfolio construction process did not center on sector selection. The conflicting results in the first report warned us to reconsider our analysis.

This change of grouping clarifies how the portfolio was constructed (whether intentional or not). In retrospect, our mistake was the decision to group the report by sector. In this case, the portfolio construction process did not center on sector selection. The conflicting results in the first report warned us to reconsider our analysis.

Risk-based performance attribution has many positive qualities in and of itself. When combined with Brinson attribution, it is a classic case of the whole being greater than the sum of the parts and that means a more complete analysis that leads to more confident conclusions.

Get new Taking Risk entries delivered to your e-mail as they are posted.

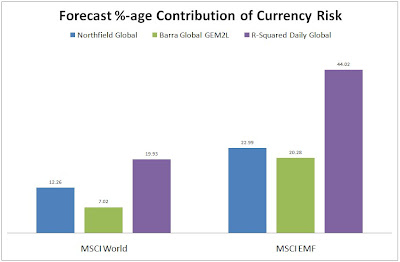

We can see that in both cases the contribution to performance on currency was very material.

We can see that in both cases the contribution to performance on currency was very material.